Core Impact

The Core Endures

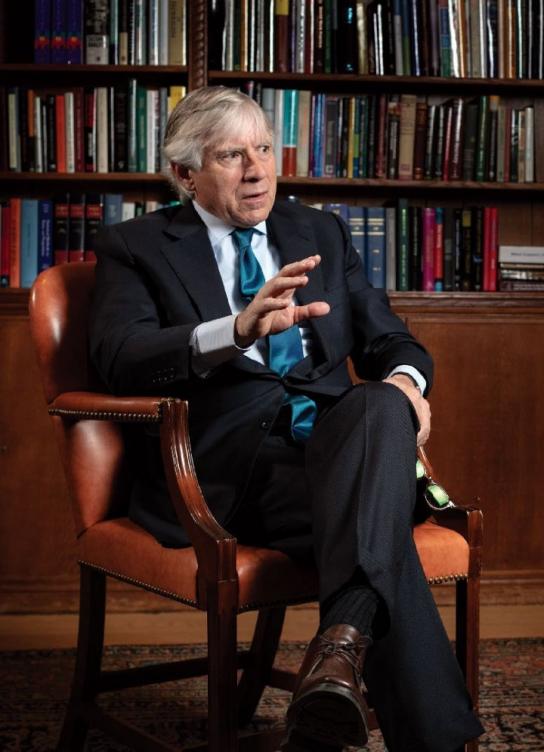

President Lee C. Bollinger sits for a conversation about the Core and its significance, not only to the College but also to the University and, more broadly, as testament to the far-reaching benefits of a liberal arts education.

As our alumni and faculty well know, this set of common courses — required of all undergraduates — is one of the defining experiences of a College education. It began in 1919 with the class that became Contemporary Civilization and evolved and expanded in the decades that followed to embrace Literature Humanities, Music Humanities, Art Humanities, University Writing (formerly Logic & Rhetoric) and, most recently, Frontiers of Science. To kick off this year of celebration and reflection, we asked President Lee C. Bollinger to sit for a conversation about the Core and its significance, not only to the College but also to the University and, more broadly, as testament to the far-reaching benefits of a liberal arts education.

What do you think makes the Core Curriculum unique and enduring?

I think it’s fair to say that, for a number of reasons, it’s almost impossible for any university in today’s world to put together core knowledge as meaningful as Columbia’s Core Curriculum. One reason for that is, it’s very difficult to get a current consensus. The challenge when you’re trying to create something new is different than when you’re taking something that’s inherited and trying to evolve it.

Many people find the Core to be intellectually thrilling. To be a young person and to be exposed to great texts, great objects of art, and great music of the world over time — and to be exposed to that directly, not intermediated by some secondary or tertiary texts or lectures — is an experience they will never forget. It is reflected in the thousands of comments I have received from current students and alums who say, “The Core changed my life.” We all feel a need to connect great thought, great beauty and great achievements to our current lives. The Core is a concentrated, very direct way of making that experience available to young people, which I think is part of its enduring legacy.

It’s really so much more than a course of study.

Absolutely. The Core offers an introduction into the scholarly mind. A university is not just a place where knowledge is transferred from one generation to the next; it’s a community, a culture. It is a way of thinking, a way of life, a way of approaching almost everything you experience over the course of a life. It encourages a sense of modesty, a sense of your own ignorance, a need to use reason and logic in constructing how you’re going to think. You are introduced to that immediately through the Core, and that is very special.

It’s also important to recognize that you don’t necessarily have an expert teaching you. It will be a serious scholar, but it may be someone coming to the subject with fresh eyes. And so, very early on as a student, you understand that you don’t have to be intimidated by expertise. It’s powerful to be told and shown by example that even though you aren’t as well equipped as someone else might be, it’s still your responsibility — and your life will be made better by making the effort — to understand.

You’re speaking, of course, about the seminar-style format of the Core. Are there other benefits to that approach?

One of the things about having to speak and write is that it makes you confront your own ignorance, your own incapacities. It’s very easy to sit back and be critical when other people are speaking — to think, “That’s all completely obvious.” But as soon as you try to write, and as soon as you try to explain things, you have to confront the fact of how difficult it is. If it were so easy to absorb Shakespeare or Montaigne or Aristotle or Virginia Woolf, we wouldn’t need universities, and we wouldn’t need the Core Curriculum.

Every person has had the experience, I think, of reading a great text, looking at a great piece of art or listening to a fine piece of music and thinking certain things, admiring certain things — but imagine then having a scholar help you to unravel that art’s complexities. You would begin to see things that you hadn’t, and it’s amazing, and by the end you develop a habit of mind; you know that you will never take a great work or any work for granted, and that, too, is an enormous educational benefit, a life benefit.

There seems to be enormous benefit as well in the community learning aspect of the Core.

Early on in my presidency, somebody in my family said that it was striking to walk up the Low Steps and to see so many students sitting quite separately, reading Plato or Aristotle. And that symbol of a young person on the Steps, outdoors, reading the same great text as someone sitting a few yards away, is an example of what you’re talking about. When you are doing the same thing that all of your peers are doing, it reinforces the seriousness of what it is that you are undertaking. I think it also must be incredibly stimulating to be able to compare notes about classes and readings; it’s an immediate bond with other individuals. The objective, of course, is to give our students so much more than the skills they need to read a great text. We want them to understand the value of being able to discuss difficult and important ideas with other people who may not share their views. We want them to continue to do it throughout their lives.

How do you view the questions around diversity and representation in the Core?

There has to be an ongoing discussion about the character and the content of the Core. And not only about the Core, but also about scholarship generally — any university worth its salt will embrace that continual self-examination and self-criticism. Issues of inclusiveness need to be addressed. Issues of a more international and global world need to be addressed. Issues about the unfairness and inequality that informed or characterized the societies in which many of these works arose or emerged need to be addressed. It’s all part of what it means to be an institution that respects reason and knowledge, and to carry forward values that we, over time, have come to realize are incredibly important — values of equality, values of addressing invidious discrimination, values of being respectful of other people, of being tolerant. So, I think the measure of the continuing success of the Core Curriculum will be its capacity to change as new values are introduced and old values are rethought.

You’ve said that “the education afforded by the Core has never been more relevant to the world we inhabit.” Can you elaborate?

We’re living at a moment when the attack on basic facts, on the use of reason, on reporting on what you see in the world — these are under assault. In one sense, there has always been anti-intellectualism in societies and certainly in American society. Universities have to contend with that, and they have to address it. But, in today’s world, this anti-intellectualism is essentially an assault on what it is that universities stand for. So, universities, and the Core Curriculum in particular, need to continue to be sources of responses to those attacks. After all, our mission, ultimately, is to discover new knowledge and pursue the truth.

How do you view the Core’s place and mission within the larger University?

The Core is, of course, the signature program of the College — but we have 16 schools here. So, I have said, and will say again, that the Core Curriculum is to the University what the University is to the world and the nation. It’s easy to say we are about the search for truth, and that can sound banal, cliché. But underlying those words is a whole tradition of respecting human inquiry into truth, knowledge and understanding. That tradition of inquiry has brought enormous benefits to the world — capitalism, free markets, open economies, political systems of self-government, democracies — and these are really, really important. But what’s incredibly important, what underlies those systems and organization of societies, is a respect for truth and a desire to expand your knowledge.

I believe in universities. They are very special institutions, and I think part of America’s success as a country is rooted in its commitment to colleges and universities and what they represent — liberal arts education, professional education, and not just in terms of preparing people for professions, but also educating people in the broadest sense. But universities are fragile. They’re different from the rest of society, and they emphasize certain values — reason and explanation; respect for different points of view; being skeptical, being modest. We take all of those values to an extreme and that creates a culture. The Core Curriculum is the essence of that and representative of what we do at all of Columbia’s schools. Studying the Core exposes our students to the best of this culture and prepares them to carry forward this way of thinking into the world.

"The Core Endures" originally appeared in the Fall 2019 issue of Columbia College Today.

Lee C. Bollinger became Columbia University’s nineteenth president in 2002. Under his leadership, Columbia stands again at the very top rank of great research universities, distinguished by comprehensive academic excellence, historic institutional development, an innovative and sustainable approach to global engagement, and unprecedented levels of alumni involvement and financial stability.

President Bollinger is Columbia’s first Seth Low Professor of the University, a member of the Columbia Law School faculty, and one of the country’s foremost First Amendment scholars. Each fall semester, he teaches “Freedom of Speech and Press” to Columbia undergraduate students. His latest book, The Free Speech Century, co-edited with Geoffrey R. Stone, was published in 2018.

Please log in to comment.