Literature

An Epic New Journey for 'The Odyssey'

Emily Wilson first encountered The Odyssey as an eight-year-old, when she played the goddess Athena in a kid-friendly production of Homer’s epic Greek poem in Oxford, England.

She was captivated by Odysseus’ struggle to survive after the Trojan War and return home to his long-suffering wife, Penelope. At Oxford University she studied classics and philosophy and earned her Ph.D. in classics and comparative literature at Yale. She is now a professor of classical studies at the University of Pennsylvania.

Her decades-long passion for the second oldest foundational poem in the Western literary canon culminated in her becoming the first woman to translate it into English. And last fall, her decidedly feminist and modern take on the classic text, published in 2017, was added to Columbia’s Core Curriculum, which will celebrate its centennial in the 2019-2020 academic year.

“All translations are interpretations, so of course it matters that I’m a woman,” said Wilson. “Social identities, including gender identities, matter for any kind of interpretive work. Being a historian, a scholar, a journalist or a translator is a development of who you are, what your embodied state is, what your personal histories might be.”

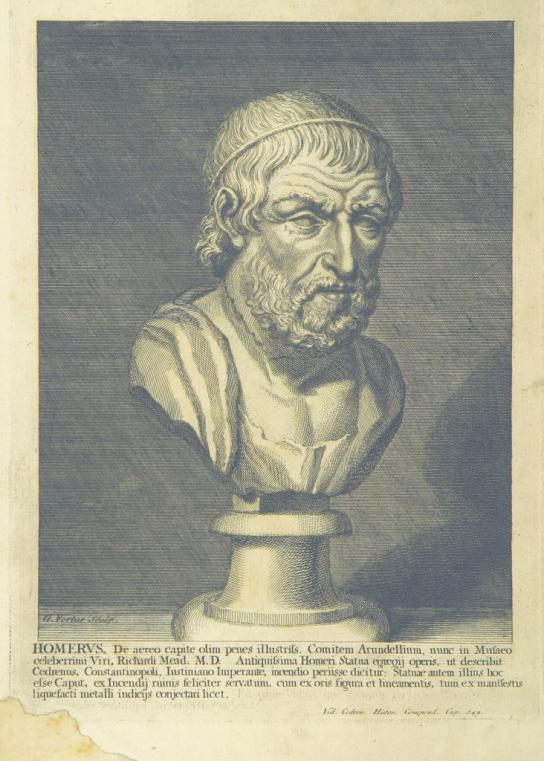

Image of bust of Homer. Homer is the name associated since antiquity with the authorship of the Iliad and Odyssey, the so-called Homeric Hymns, and some other poems (mostly not extant). Nothing is recorded of him as a historical person; ancient biographical accounts contain nothing reliable, being compilations from apocryphal stories, competing local claims, and imaginative inferences from the poems.

There have been more than 60 English translations of the Homeric work since the first, in 1615, by poet and dramatist George Chapman. Since 1967, Columbia students used a version by Richard Lattimore.

“Wilson’s translation is utterly fresh, exciting, moving and new,” said Julie Crawford, the Mark Van Doren Professor of Humanities, who was involved in the decision to use the new translation in the Core Curriculum.

“Why is it so important that Wilson is a she?” asked Joanna Stalnaker, the Paul Brooke Program Chair for Literature Humanities. “There’s a sense of the epic as a masculine genre and Homer’s status as the pinnacle of that genre. With Wilson, it’s a question of whose stories get told, whose voices are listened to. This is all so central now, not only to The Odyssey, but also to our own political moment with the Me Too movement.”

Wilson’s version stakes out new territory from its very first line. The poem starts, “Tell me about a complicated man.” The Greek word that she translated as “complicated” is polytropos, one of Homer’s regular epithets for Odysseus, which literally means “many turned” or “much turning.” It connotes his duplicity, his cunning and suffering, his wanderings, what he does and what is done to him on his journey home.

By contrast, the Lattimore edition begins, “Tell me, Muse, of the man of many ways.”

Wilson believes that many previous Odyssey translations imposed a much more singular perspective on the poem than the original had. “I wanted to bring out these multiple different points of view,” she said. “For example, the way Penelope sees her marriage is not the same as the way Odysseus sees his marriage.”

Where Odysseus has many choices about what to do, where to go and whom to see, as a married woman Penelope has only one: to wait years for her husband to return, or to marry someone else. And this option has a time limit because her abusive suitors can force her to act against her will.

When he finally returns, Odysseus slaughters the suitors and tells his son Telemachus to kill the dozen female slaves who have slept with the suitors in order to regain his property and status. The murdered slaves are described in some English translations as disobedient maids—giving the text “a Downton Abbey feel,” said Wilson—and in others as “sluts” or “whores.”

“This is a level of verbal, misogynistic abuse that finds no analogue in the Greek,” continued Wilson. “I read Homer’s great poem as a complex and truthful articulation of gender dynamics that continue to haunt us. Part of my job is to make visible the cracks in this patriarchal fantasy.”

Another major aim of Wilson’s approach was to preserve the ancient Greek oral tradition for a modern audience, which she achieved through using iambic pentameter, the English epic’s equivalent of Greek dactylic hexameter. The result is a direct, fast-moving verse of almost conversational English that is the same number of lines as the original poem.

“Because Wilson maintains what she calls ‘Homer’s nimble gallop,’ her translation is both shorter and more accessible than Lattimore’s, making it a good choice for the Lit Hum syllabus, where we face the challenge of teaching The Odyssey in just three class sessions,” said Stalnaker.

Please log in to comment.