Lit Hum Revisited

David Denby ’65, ’66J is a familiar name to readers of The New Yorker; he has been a staff writer and film critic at the magazine since 1998. Earlier, he was the film critic for New York magazine for 20 years and won a 1991 National Magazine Award. During his time at New York, Denby returned to the Morningside Heights campus and his Core Curriculum roots and retook Literature Humanities and Contemporary Civilization. The result was the New York Times bestseller GREAT BOOKS: My Adventures with Homer, Rousseau, Woolf, and Other Indestructible Writers of the Western World (1997). In the excerpt that follows, he relates his struggles as an older student wrestling in his middle years with the slippery classics of Lit Hum, in particular, The Iliad. Denby’s other books include Do the Movies Have a Future? (2012), Snark (2009) and American Sucker (2004).

In the fall of 1991, thirty years after entering Columbia University for the first time, I went back to school and sat with eighteen-year-olds and read the same books that they read. Not just any books. Together we read Homer, Plato, Sophocles, Augustine, Kant, Hegel, Marx, and Virginia Woolf. Those books. Those courses — the two required core-curriculum courses that I had first taken in 1961, innocently and unconsciously, as a freshman at Columbia College. No one in that era could possibly have imagined that in the following decades the courses would be alternately reviled as an iniquitous oppression and adored as a bulwark of the West.

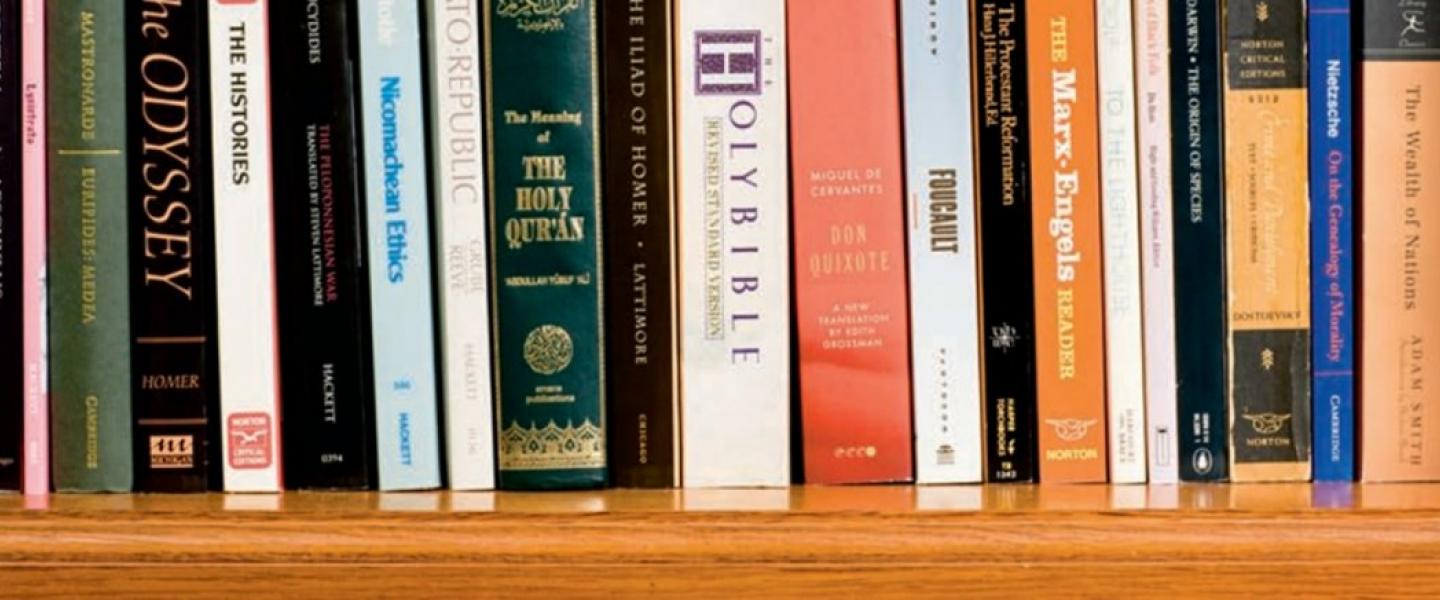

One of the courses, Literature Humanities, or Lit Hum, as everyone calls it, is (and was) devoted to a standard selection of European literary masterpieces; the other, Contemporary Civilization, or C.C., offers a selection of philosophical and social-theory masterpieces. They are both “great books” courses, or, if you like, “Western civ” surveys, a list of heavyweight names assembled in chronological order like the marble busts in some imaginary pantheon of glory. Such courses were first devised, earlier in the century, at Columbia; they then spread to the University of Chicago, and in the 1940s to many other universities and colleges. They have since, putting it mildly, receded. At times, they have come close to extinction, though not at Columbia or Chicago.

Despite my explanations, my fellow students in 1991 may well have wondered what in the world I was doing there, sitting in uncomfortable oak-plank chairs with them. I was certainly a most unlikely student: forty-eight years old, the film critic of New York magazine, a husband and father, a settled man who was nevertheless unsettled in some way that may not have been any clearer to me than it was to them. Was it just knowledge I wanted? I had read many of the books before. Yet the students may have noticed that nothing in life seemed more important to me than reading those books and sitting in on those discussions.

The project began when my wife suggested that I put up or shut up. In 1989 or 1990, somewhere back there, Cathleen Schine and I were reading, with increasing amazement, the debate about the nature of higher education in this country. Merely reciting the cliches of the debate now induces a blue haze of exasperation and boredom: What role should the Western classics and a “Eurocentric” curriculum play in a country whose population was made up of people from many other places besides Europe — for instance, descendants of African slaves and American Indians? Should groups formerly without much power — women, as well as minorities — be asked to read through a curriculum dominated by works written by Dead White European Males?

I began to suffer from an increasing sense of unreality.

Thirty years earlier, I had enjoyed Lit Hum and C.C.

a great deal, but then had largely forgotten them,

as one forgets most college courses one takes.

The questions were not in themselves unreasonable, but it now seems hard to believe that anyone above sixteen could possibly have used, as a term of blame, the phrase “Dead White European Males.” The words have already taken on a quaint period feel, as moldy as the love beads that I wore once, in the spring of 1968, and then flung into the back of a dresser drawer. Such complaints, which issued generally from the academic left, especially from a variety of feminist, Marxist, and African-American scholars, were answered in turn by conservatives with resoundingly grandiose notions of the importance of the Western tradition for American national morale. In their consecutive stints as chair of the National Endowment for the Humanities, William Bennett and Lynne V. Cheney said some good things about the centrality of the humanities in the life of an educated person. But the clear implication of their more polemical remarks was that if we ceased to read the right books, we could not keep Communism or relativism — or whatever threatened the Republic — at the gates. There were national, even geopolitical considerations at stake. Literature had become a matter of policy.

As I made my way through the debate, I began to suffer from an increasing sense of unreality. Thirty years earlier, I had enjoyed Lit Hum and C.C. a great deal, but then had largely forgotten them, as one forgets most college courses one takes. Exactly how the books for the courses had remained in my mind, as a residue of impressions and a framework of taste and sensibility, and even of action, I could not say. That was the mystery, wasn’t it? — the mystery of education. Exactly how does it matter to us? The participants in the debate, however, seemed to know. They made extravagant claims for or against the books and the Western tradition the books embodied. At the same time, they discussed the books themselves — works of literature, philosophy, and political theory — in an unpleasantly featureless and abstract way that turned them into mere clubs and spears in an ideological war. Shakespeare an agent of colonialism? Rousseau part of the “hegemonic discourse”? The Greek classics a bulwark of democracy? Was it really literature and philosophy that people were discussing in such terms? One had the uncanny sense that at least some of the disputants hadn’t bothered to read the books in question in more than twenty years. Could such classic works actually be as boring as the right — or as wicked as the left — was making them sound? The books themselves had been robbed of body and flavor. And in so many of the polemics, the act of reading itself had become hollowed out — emptied of its place in any reader’s life, its stresses and pleasures, its boredom, its occasional euphoria. It had lost its special character of solitude and rapture.

Yet strange as the debate seemed to me, it had a galvanizing effect. For months, I was angry and even pained. I felt I had been cheated of something, and it didn’t take long to realize why. If some of the disputants appeared to be far away from the books in question, I knew that I was far away from them, too. I had read, I had forgotten, and I felt the loss as I did the loss of an old friend who had faded away.

I worked myself into a high state of indignation, and Cathy, both a novelist and a reader, shared my view but grew tired of my outrage. There she sat in our apartment in New York, reading book after book, in bed, in the living room, at the chair by the living-room window. Often she read with a cat in her lap, the animal happily purring; its mistress, lost in her reading, scratched its head for hours. My wife was too kind, and perhaps too busy, to point out something that later seemed obvious: I had become something of a nonreader myself; or, let us say, a reader of journalism, public-affairs books, and essays on this or that. “If you’re so upset about this,” Cathy finally said, “why don’t you take your Columbia courses again?”

Thus the revenge of the reader on the nonreader: why don’t you read and stop complaining? Certainly the means to answer my questions lay at hand. Columbia was only a couple of miles from my apartment on the West Side of Manhattan. And the courses, though somewhat different in their selection of texts, had not changed much in conception.

Reading “the great books” may seem an odd solution to a “midlife crisis” or a crisis of identity, or whatever it was. Why not travel or hunt elephants? Chase teenage girls? Live in a monastery? These, I believe, are the traditional methods — for men, at least — of dealing with such problems. But if I wanted adventure, I wanted it in a way that made sense for me. Reading seriously, I thought, might be one way of ending my absorption in media life, a way of finding the edges again.

But why not just sit and read? Why go back to Columbia? Because I wanted to see how others were reading — or not reading. The students had grown up living in the media. What were they like? What had happened to teaching in the age of the culture debate, in a corner of the university far from the war yet obviously touched by the noise of battle? One way of dispelling the crudities and irrelevancies of the “culture wars” was to find out what actually went on in classrooms.

And I wanted to add my words to the debate from the ground up, beginning and ending in literature, never leaving the books themselves.

I had forgotten. I had forgotten the extremity of its cruelty and tenderness, and, reading it now, turning The Iliad open anywhere in its 15,693 lines, I was shocked. A dying word, “shocked.” Few people have been able to use it well since Claude Rains so famously said, “I’m shocked, shocked to find that gambling is going on here,” as he pocketed his winnings in Casablanca. But it’s the only word for excitement and alarm of this intensity. The brute vitality of the air, the magnificence of ships, wind, and fires; the raging battles, the plains charged with terrified horses, the beasts unstrung and falling; the warriors flung facedown in the dust; the ravaged longing for home and family and meadows and the rituals of peace, leading at last to an instant of reconciliation, when even two men who are bitter enemies fall into rapt admiration of each other’s nobility and beauty — it is a war poem, and in the Richmond Lattimore translation it has an excruciating vividness, an obsessive observation of horror that causes almost disbelief.

Simoeisios in his stripling’s beauty, whom once his mother descending from Ida bore beside the banks of Simoeis when she had followed her father and mother to tend the sheepflocks. Therefore they called him Simoeisios; but he could not render again the care of his dear parents; he was short-lived, beaten down beneath the spear of high-hearted Aias, who struck him as he first came forward beside the nipple of the right breast, and the bronze spearhead drove clean through the shoulder. He dropped then to the ground in the dust, like some black poplar … (IV, 472-82)

The nipple of the right breast. Homer in his terrifying exactness tells us where the spear comes in and goes out, what limbs are severed; he tells us that the dead will not return to rich soil, they will not take care of elderly parents, receive pleasure from their young wives. His explicitness has a finality beyond all illusion. In the end, the war (promoted by the gods) will consume almost all of them, Greeks and Trojans alike, sweeping on year after year, in battle after battle — a mystery in its irresistible momentum, its profoundly absorbing moment-to-moment activity and overall meaninglessness. First one side drives forward, annihilates hundreds, and is on the edge of victory. Then, a few days later, inspired by some god’s trick or phantasm — a prod to the sluggish brain of an exhausted warrior — the other side recovers, advances, and carries all before it. When the poem opens, this movement back and forth has been going on for more than nine years.

The teacher, a small, compact man, about sixty, walked into the room, and wrote some initials on the board:

W A S P

D W M

W C

D G S I

While most of us tried to figure them out (I had no trouble with the first two, made a lame joke to myself about the third, and was stumped by the fourth), he turned, looking around the class, and said ardently, almost imploringly, “We’ve only got a year together. … ” His tone was pleading and mournful, a lover who feared he might be thwarted. There was an alarming pause. A few students, embarrassed, looked down, and then he said: “This course has been under attack for thirty years. People have said” — pointing to the top set of initials — “the writers are all white Anglo-Saxon Protestants. It’s not true, but it doesn’t matter. They’ve said they were all Dead White Males; it’s not true, but it doesn’t matter. That it’s all Western civilization. That’s not quite true either — there are many Western civilizations — but it doesn’t matter. The only thing that matters is this.”

He looked at us, then turned back to the board, considering the initials “DGSI” carefully, respectfully, and rubbed his chin. “Don’t Get Sucked In,” he said at last. Another pause, and I notice the girl sitting next to me, who has wild frizzed hair and a mass of acne on her chin and forehead, opening her mouth in panic. Others were smiling. They were freshmen — sorry, first-year students — and not literature majors necessarily, but a cross-section of students, and therefore future lawyers, accountants, teachers, businessmen, politicians, TV producers, doctors, poets, layabouts. They were taking Lit Hum, a required course that almost all students at Columbia take the first year of school. This may have been the first teacher the students had seen in college. He wasn’t making it easy on them.

“Don’t get sucked in by false ideas,” he said. “You’re not here for political reasons. You’re here for very selfish reasons. You’re here to build a self. You create a self, you don’t inherit it. One way you create it is out of the past. Look, if you find The Iliad dull or invidious or a glorification of war, you’re right. It’s a poem in your mind; let it take shape in your mind. The women are honor gifts. They’re war booty, like tripods. Less than tripods. If any male reading this poem treated women on campus as chattel, it would be very strange. I also trust you to read this and not go out and hack someone to pieces.”

Ah, a hipster, I thought. He admitted the obvious charges in order to minimize them. And he said nothing about transcendental values, supreme masterpieces of the West, and the rest of that. We’re here for selfish reasons. The voice was pleasant but odd — baritonal, steady, but with traces of mockery garlanding the short, definitive sentences. The intonations drooped, as if he were laying black crepe around his words. A hipster wit. He nearly droned, but there were little surprises — ideas insinuated into corners, a sudden expansion of feeling. He had sepulchral charm, like one of Shakespeare’s solemnly antic clowns.

I remembered him well enough: Edward “Ted” Tayler, professor of English. I had taken a course with him twenty-nine years earlier (he was a young assistant professor then), a course in seventeenth-century Metaphysical poetry, which was then part of the sequence required for English majors at Columbia, and I recalled being baffled as much as intrigued by his manner, which definitely tended toward the cryptic. He was obviously brilliant, but he liked to jump around, keep students off balance, hint and retreat; I learned a few things about Donne and Marvell, and left the class with a sigh of relief. In the interim, he had become famous as a teacher and was now the sonorously titled Lionel Trilling Professor in the Humanities — the moniker was derived from Columbia’s most famous English literature professor, a great figure when I was there in the early sixties.

“You may not believe that God created the universe,”

Tayler said, mournful, sepulchral, “but, anyway, look what God is doing in this passage. He’s setting up opposites.

Which is something we do all the time in life.”

“The Hermeneutic Circle,” Tayler was saying. “That’s what Wilhelm Dilthey called it. You don’t know what to do with the details unless you have a grip on the structure; and at the same time, you don’t know what to do with the structure unless you know the details. It’s true in life and in literature. The Hermeneutic Circle. It’s a vicious circle. Look, we have only a year together. You have to read. There’s nothing you’ll do in your four years at Columbia that’s more important for selfish reasons than reading the books of this course.”

Could they become selves? From my position along the side of the classroom, I sneaked a look. At the moment they looked more like lumps, uncreated first-year students. The men sat with legs stretched all the way out, eyes down on their notes. Some wore caps turned backward. They were eighteen, maybe nineteen. In their T-shirts, jeans, and turned-around caps, they had a summer-camp thickness, like counselors just back from a hike with ten-year-olds. Give me a beer. The women, many of them also in T-shirts, their hair gathered at the back with a rubber band, were more directly attentive; they looked at Tayler, but they looked blankly.

Tayler handed out a sheet with some quotations. At the top of the page were some verses from the beginning of Genesis:

And God said, Let there be light; and there was light. And God saw the light, that it was good: And God divided the light from the darkness. … And God said, Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters.

“You may not believe that God created the universe,” Tayler said, mournful, sepulchral, “but, anyway, look what God is doing in this passage. He’s setting up opposites. Which is something we do all the time in life. Moral opposites flow from binary opposites. There are people you touch, and people you don’t touch. Every choice is an exclusion. How do you escape the binary bind? Look, St. Augustine, whom we’ll read later, says that before the Fall there were no involuntary actions. Before the Fall, Adam never had an involuntary erection.” Pause, pause. … “If Adam and Eve wanted to do something, they did it. But you guys are screwed up; you’re in trouble. There’s a discrepancy between what you want to do and what you ought to do. You want to go out and have a beer with friends, and you have to force yourself through a series of battles. After the Fall, you fall into dualities.”

There were other quotations on the sheet, including one from John Milton, but Tayler didn’t say right then what their significance might be. He looked around. Was anyone getting it? Maybe. Was I? We would see. Then he turned all loverlike and earnest once more. And he said it again. “Look, keep a finger on your psychic pulse as you go. This is a very selfish enterprise.”

By the time the action of The Iliad begins, the deed that set off the whole chain of events — a man making off with another man’s wife — is barely mentioned by the participants. Homer, chanting his poetry to groups of listeners, must have expected everyone to know the outrageous old tale. Years earlier, Paris, a prince of Troy, visiting the house of the Greek king Menelaus, took away, with her full consent, Helen, the king’s beautiful wife. Agamemnon, the brother of the cuckold, then put together a loose federation of kings and princes whose forces voyaged to Troy and laid siege to the city, intending to punish the proud inhabitants and reclaim Helen. But after more than nine years of warfare, the foolish act of sexual abandonment that set the whole cataclysm in motion has been largely forgotten. By this time, Helen, abashed, considers herself merely a slut (her embarrassed appearance on the walls of Troy is actually something of a letdown), and Paris, her second “husband,” more a lover than a fighter, barely comes out to the battlefield. When he does come out, and he and Menelaus fight a duel, the gods muddy the outcome, and the war goes on. After nine years, the war itself is causing the war.

How can a book make one feel injured and exhilarated at the same time? What’s shocking about the Iliad is that the cruelty and the nobility of it seem to grow out of each other, like the good and evil twins of some malign fantasy who together form a single unstable and frightening personality. After all, Western literature begins with a quarrel between two arrogant pirates over booty. At the beginning of the poem, the various tribes of the Greeks (whom Homer calls Achaeans — Greece wasn’t a national identity in his time), assembled before the walls of Troy, are on the verge of disaster. Agamemnon, their leader, the most powerful of the kings, has kidnapped and taken as a mistress from a nearby city a young woman, the daughter of one of Apollo’s priests; Apollo has angrily retaliated by bringing down a plague on the Greeks. A peevish, bullying king, unsteady in command, Agamemnon, under pressure from the other leaders, angrily gives the girl back to her father. But then, demanding compensation, he takes for himself the slave mistress of Achilles, his greatest warrior. The women are passed around like gold pieces or helmets. Achilles is so outraged by this bit of plundering within the ranks that he comes close to killing the king, a much older man. Restraining himself at the last minute, he retires from the combat and prays to his mother, the goddess Thetis, for the defeat of his own side; he then sits in his tent playing a lyre and “singing of men’s fame” (i.e., his own) as his friends get cut up by the Trojans. What follows is a series of battles whose savagery remains without parallel in our literature.

It is almost too much, an extreme and bizarre work of literary art at the very beginning of Western literary art. One wants to rise to it, taking it full in the face, for the poem depicts life at its utmost, a nearly ceaseless activity of marshaling, deploying, advancing, and fleeing, spelled by peaceful periods so strenuous — the councils and feasts and games — that they hardly seem like relief at all. Reading the poem in its entirety is like fronting a storm that refuses to slacken or die. At first, I had to fight my way through it; I wasn’t bored but I was rebellious, my attention a bucking horse unwilling to submit to the harness. It was too long, I thought, too brutal and repetitive and, for all its power as a portrait of war, strangely distant from us. Where was Homer in all this? He was everywhere, selecting and shaping the material, but he was nowhere as a palpable presence, a consciousness, and for the modern reader his absence was appalling. No one tells us how to react to the brutalities or to anything else. We are on our own. Movie-fed, I wasn’t used to working so hard, and as I sat on my sofa at home, reading, my body, in daydreams, kept leaping away from the seat and into the bedroom, where I would sink into bed and turn on the TV, or to the kitchen, where I would open the fridge. Mentally, I would pull myself back, and eventually I settled down and read and read, though for a long time I remained out of balance and sore.

Other men may have more active recollections — scoring a goal, kissing a girl at the homecoming game, all that autumn-air, pocket-flask, Scott Fitzgerald stuff — but my sweetest memory of college is on the nuzzling, sedate side. At the beginning of each semester, I would stand before the books required for my courses, prolonging the moment, like a kid looking through the store window at a bicycle he knows his parents will buy for him. I would soon possess these things, but the act of buying them could be put off. Why rush it? The required books for each course were laid out in shelves in the college bookstore. I would stare at them a long time, lifting them, turning through the pages, pretending I didn’t really need this one or that, laying it down and then picking it up again. If no one was looking, I would even smell a few of them and feel the pages — I had a thing about the physical nature of books, and I was happy when I realized that my idol, the great literary critic Edmund Wilson, was obsessed with books as sensuous objects.

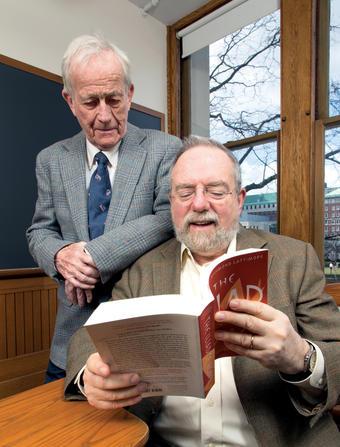

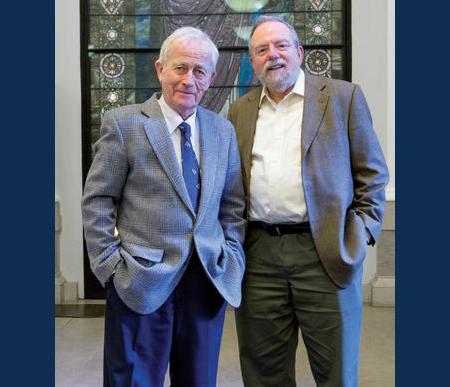

Denby (right) studied Lit Hum under Tayler (left) as an undergraduate and again 30 years later when he took the course as an alumnus and wrote Great Books.

Obviously, it wasn’t just learning that excited me but the idea of reading the big books, the promise of enlargement, the adventure of strangeness. Reading has within it a collector’s passion, the desire to possess: I would swallow the whole store. Reality never entered into this. The difficulty or tedium of the books, the droning performance of the teacher — I might even have spent the entire previous semester in a self-absorbed funk, but I roused myself at the beginning of the new semester for the wonderful ritual of the bookstore. Each time I stood there, I saw myself serenely absorbing everything, though I was such an abominably slow reader, chewing until the flavor was nearly gone, that I never quite got around to completing the reading list of any course.

And so it has been ever since. Walking home from midtown Manhattan, I am drawn haplessly to a bookstore — Coliseum Books, at Broadway and Fifty-seventh, will do — where I will buy two or three books, which then, often enough, sit on my shelves for years, unread or partly read, until finally, trying to look something up, I will pull one or another out, bewildered that I have it. I like to own them: I had grown into a book-buyer but not always a book-reader; a boon to the book trade, perhaps, but not a boon to myself.

At the age of forty-eight, I stood in front of the shelves in Columbia’s bookstore at 115th Street and Broadway, a larger and better-lit place than the store in my day, which was so tightly packed one never got away from that slightly sweet smell that new books have. I was absurdly excited. There they were, the books for the Lit Hum and C.C. courses: the two thick volumes of Homer; the elegant Penguin editions of Aeschylus and Hobbes, with their black borders and uniform typeface; the rather severe-looking academic editions of Plato and Locke, all business, with no designs on the cover or back, just the titles, and within, rows of virtuously austere type. They were as densely printed as lawbooks. I was thrilled by the possibility that they might be difficult. I would read; I would study; I would sit with teenagers.

From GREAT BOOKS by David Denby. Copyright © 1996 by David Denby. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Originally appeared in CCT, Spring 2013.

Please log in to comment.