Core Impact

A Short History of the Core

“Justice...is not to be achieved simply by good intentions, but must be preceded by at least a little information.”

Columbia University President Nicholas Murray Butler, 1919

On the afternoon of September 25, 1919, University President Nicholas Murray Butler presided over the opening ceremonies for Columbia’s 166th academic year. Although the end of World War I less than a year earlier had officially brought peace to the nation, American life was still fraught with difficulties. The armistice was accompanied by the country’s first Red Scare; fervent nationalism, anti-foreign sentiment, and infringements on free speech and civil liberties appeared to be on the rise. In this climate, President Butler and Columbia faculty looked to education for the betterment of individuals and their communities. The “little information” that Butler hoped to impart to new students that year, in an effort to remake a world torn by war and injustice, became the Core Curriculum we know today.

Contemporary Civilization, the oldest course in Columbia’s Core Curriculum, was conceived in this spirit and introduced in the 1919-1920 academic year. It had grown out of a course on “War Issues” that the US Army had commissioned Columbia to create for the Student Army Training Corps. The Army hoped that soldiers might understand the ideals behind their military campaigns, and that the life of ideas could sustain them through their harrowing experiences in the trenches. When the war concluded, the course was re-invented as a course on “Peace Issues” and dubbed “Introduction to Contemporary Civilization in the West.”

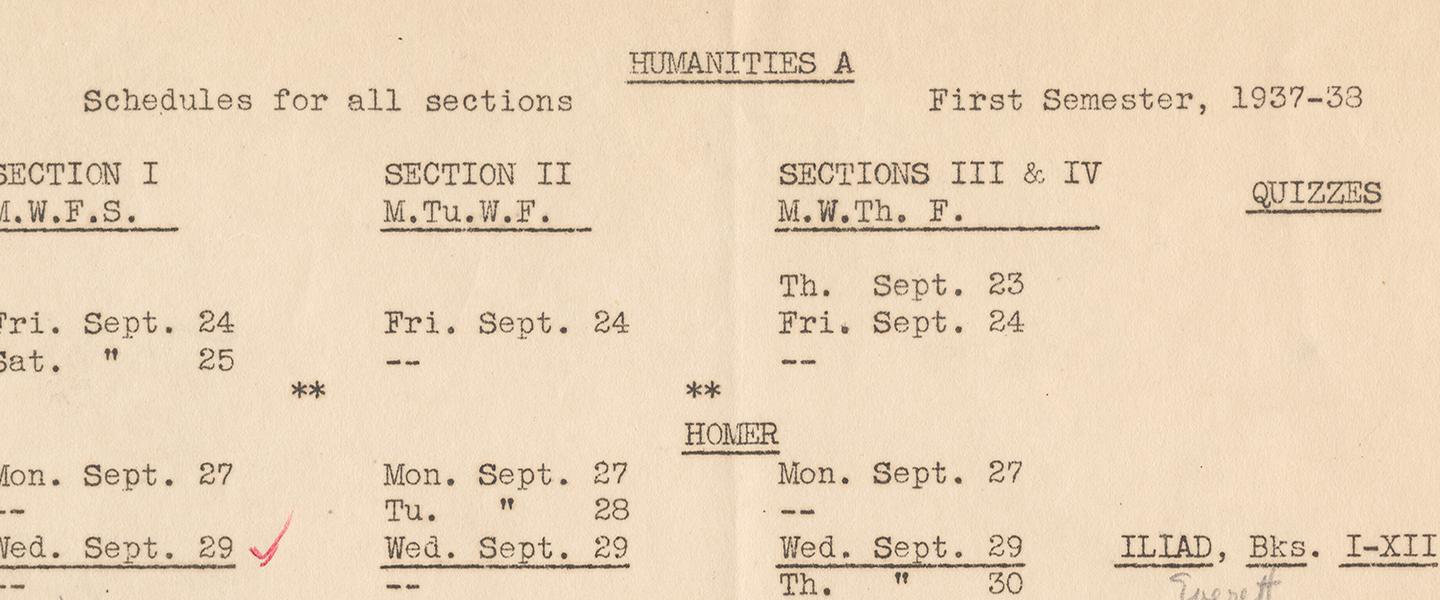

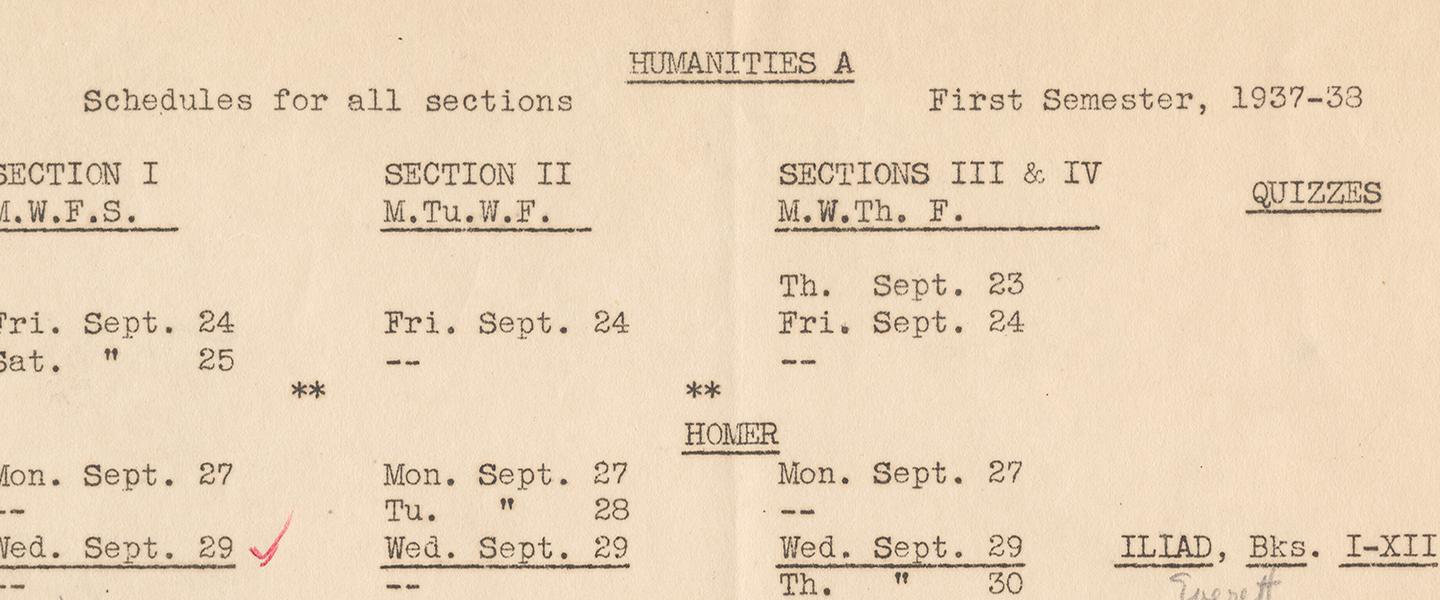

Contemporary Civilization would become the cornerstone of the ever-evolving Core Curriculum. Instruction in science appeared in the 1930s. A humanities sequence, also initiated in the 1930s, was ultimately reorganized as Art and Music Humanities in 1941 and Literature Humanities in 1962. Starting in the late 1940s, the Core expanded beyond the Western tradition with an elective called “Oriental Civilization.” And in 1985 (not coincidentally two years after the College started admitting female students) women authors finally appeared on Core class syllabi with the inclusion of Pride and Prejudice in Literature Humanities.

Core classes have always been small, focused on primary texts and discussion, and (by design) led by professors who cannot possibly be experts in all of the texts and traditions they teach. Another constant from the early days of the Core is the focus on “present problems.” Although Core texts run the gamut from ancient to postmodern, students seek to understand their relevance to today. In Core classes, Columbia students interrogate enduring works of literature, philosophy, history, and art; find arenas for fruitful engagement and disagreement; and consider the most critical questions of human life. One century into the life of the Core, during his May 2018 Commencement address, University President Lee Bollinger echoed the remarks of his predecessor President Butler: The world seemed “deeply troubled” once again, but the Core, as “a set of values and intellectual habits of mind,” remained true to its original goal as a bulwark against closed-mindedness.

1 comments

Please log in to comment.