Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959) is often considered the iconic American architect, known for buildings as diverse as the Larkin Administration Building, Falling Water, and the Guggenheim. Art Humanities students benefit not only from learning about modern architecture through a curriculum newly revised by leading architectural scholars, but also having access to the Frank Lloyd Wright archives at Avery Library, which Columbia has co-owned with MoMA since 2012. Visits to the archives, where students can see original Frank Lloyd Wright drawings and photographs, are often a favorite of Art Humanities students. Professor Barry Bergdoll, former Chief Curator for MOMA, was instrumental in this acquisition, and curated the MoMA exhibition Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive in 2017.

See below for a video of Professor Bergdoll discussing Wright's never built Mile-High Tower, from the archives.

Excerpt on the Larkin Building

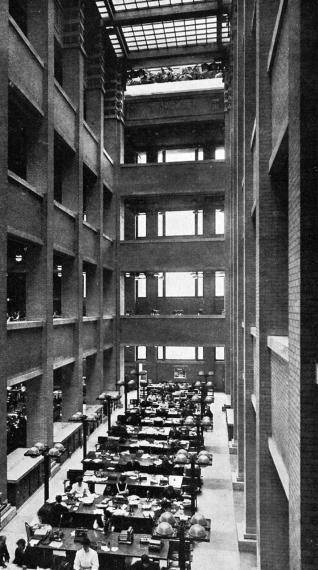

As the etymology of the word suggests, a bureaucracy is an arrangement in which power originates from a bureau. Or, in more concrete terms, bureaucratic control is exercised from behind a piece of furniture. Not coincidentally, the Larkin’s unique bureaucracy was made possible by the building’s furnishings, which, with the possible exception of the filing cabinets, were designed by Wright’s office and custom-manufactured by the Van Dorn Iron Works of Cleveland. Some of the designs were patented, despite the fact that an extensive variety of mass-produced office equipment was available at the time. So intense was the attention paid to the design of this equipment that, as Wright put it, “the building [was] its own furnishing” and “its furnishings part of the building.” This becomes clear in the compulsively detailed drawings that Wright’s office produced fro almost every piece of the building’s equipment, from the chairs, desks, and lighting fixtures to the suspended toilet bowls. In an interior perspective from the Wasmuth portfolio, these furnishings compete with the building’s much-vaunted tectonic order. Desks and chairs are carefully articulated and so too are the filing cabinets behind the heavy piers surrounding the central atrium. As Wright would note decades later, his only regrets were that his drawings for wastepaper baskets were not implemented and that he was not allowed to design the telephone apparatuses installed throughout the building.

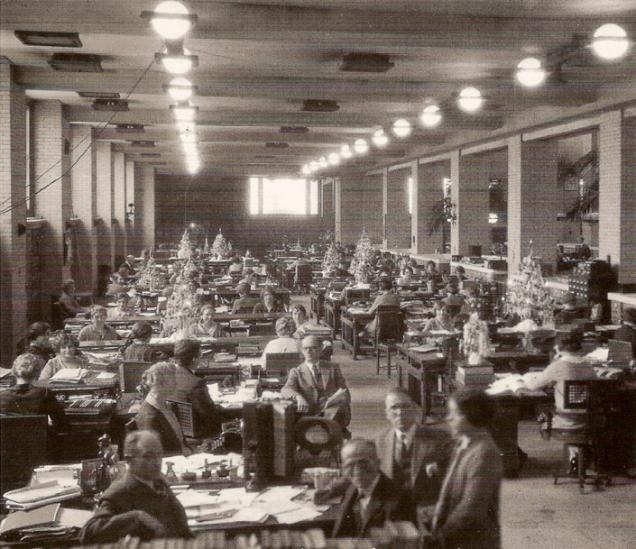

The Larkin Company’s corporate hierarchy was inscribed into these furnishings. One could tell an employee’s place in the pecking order not only from the location of his or her desk but also from its type. The building housed eighteen hundred employees, and most of these were seated at one of three types of desks. Type A desks were positioned in the atrium; each accommodated six employees, with two pairs of executives facing each other and two secretaries sitting between them. These desks, furnished with their own filing cabinets and “disappearing covers” that could be pulled out or tucked in to hide or reveal typewriters, alternated with others equipped with graphophones—Larkin-patented devices that recorded executives’ voices on wax cylinders for later transcription by typists. According to one observer, George Twitmyer, “by merely turning in his swivel chair,” an executive could switch from the desk in front of him to the one behind. Type B desks were designed for chief clerks. These incorporated stowable typewriter tables and arm-mounted chairs that swung free of the floor. Finally, Type C desks, for the hundreds of clerical workers, could be fitted with drawers, filing cabinets, or pigeonholes and had openings for graphophones. Janitors cleaned the building using a vacuum system powered by pneumatic motors, and, according to Wright, equipment such as arm-mounted chairs saved them significant effort.

The three desk types did not simply accelerate the movement of paperwork. Rather, the furniture carefully modulated the pace of workflow. While paper lingered on an executive’s type A desk, for example, storage in the clerks’ type C desks was purposefully minimized. The result, according to one account, was that “at the close of day the chairs are folded up…. The [desk]tops are also cleared of all work, papers going into one of the desk drawers, books and cards filed into the cabinets provided for them. In less than two minutes from the sounding of the time-gong every clerk’s desk in the building may be absolutely cleared, leaving not so much as a scrap of paper in sight.” If a form had to idle at a clerk’s desk, there were strict rules about how it should do so; for example, company protocols defined the right and wrong ways to pin papers. The discipline that company executives aspired to maintain through the arrangement of furniture (note that offices were frequently stage for photographs to be published in the company’s publicity material) was a point of pride for Wright. “The general scheme of the arrangement of the desk and filing system,” he wrote, “is as orderly and systemically complete as a well-disciplined army.” The varied clothing of the clerks was the only distraction from this perfect order—a distraction that would soon be eliminated, executives reportedly promised, with the introduction of uniforms.

Zeynep Çelik Alexander, “The Larkin’s Technology of Trust,” 303-307