Warhol + Basquiat

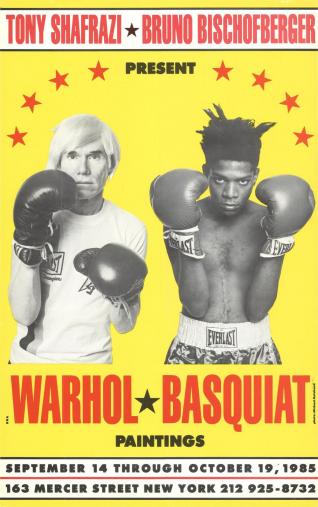

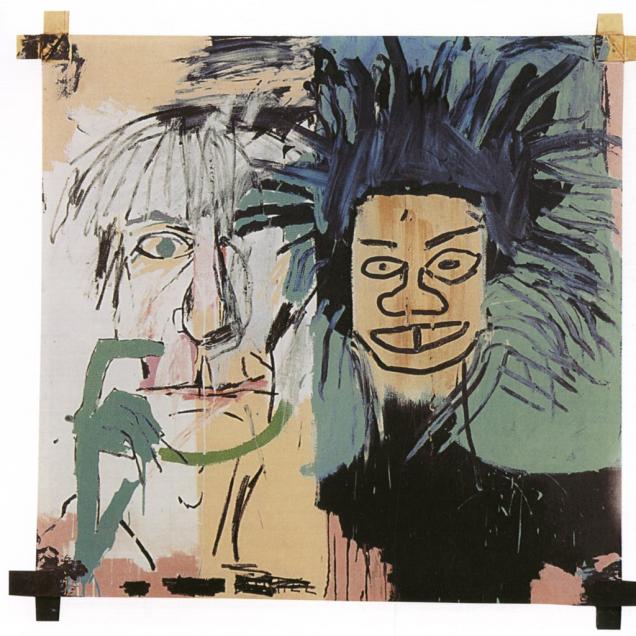

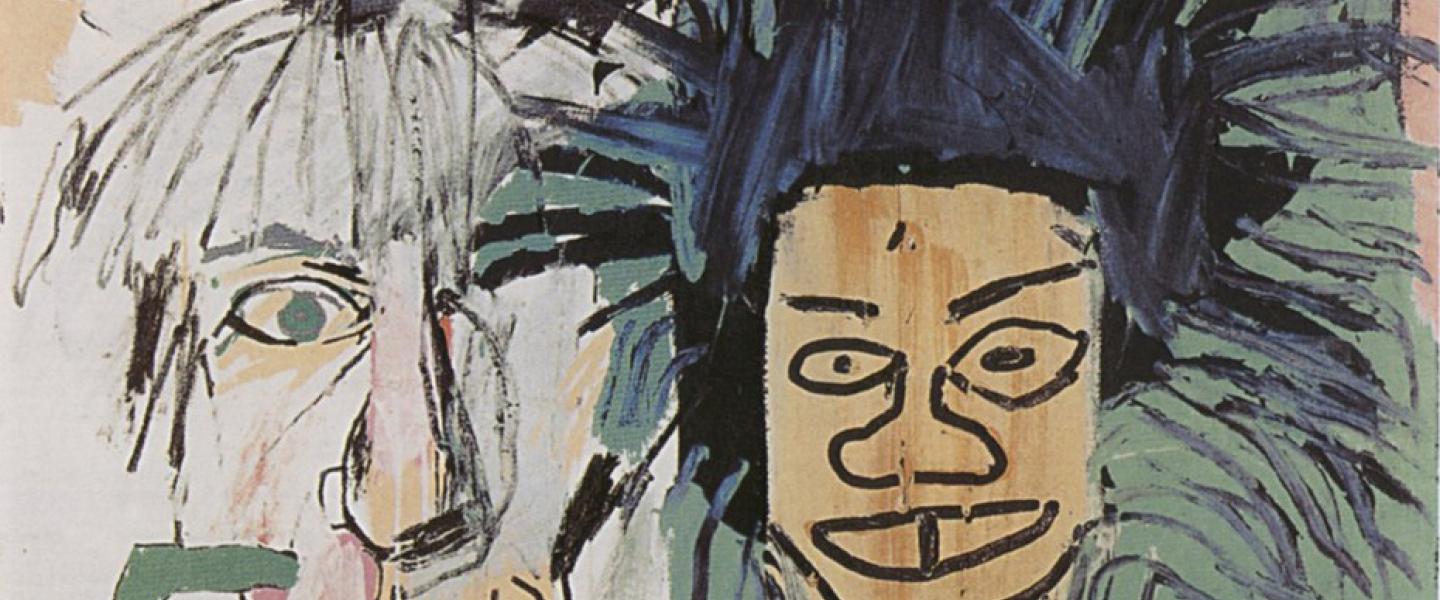

While seminal Pop artist Andy Warhol (1927-1987) has been a fixture of the the Art Humanities curriculum, Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) is one of the artists being considered for the newly revised curriculum. The pairing of Warhol and Basquiat is particularly apt due to their close relationship – Warhol at times mentored the younger artist, and they collaborated on numerous paintings, staging an exhibition of joint works in 1985.

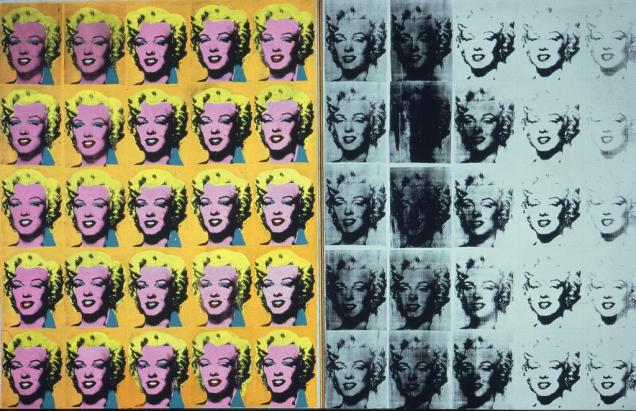

Though stylistically quite disparate, both artists drew on aspects of culture that had previously not been taken seriously in the art world: advertising imagery, consumer goods, and celebrity culture in the case of Warhol and graffiti aesthetics, sports stars, and street culture for Basquiat. Both were also sensational figures in their lifetimes, and continue to draw widespread interest and acclaim. Warhol’s 2018-2019 retrospective at the Whitney broke attendance records, while Basquiat currently holds the auction record for highest sale price of any American artist.

Read below for an excerpt from Professor Kellie Jones on Basquiat, and an excerpt from Warhol on his own work.

Excerpt from “Lost in Translation: Jean-Michel in the (re)mix,”

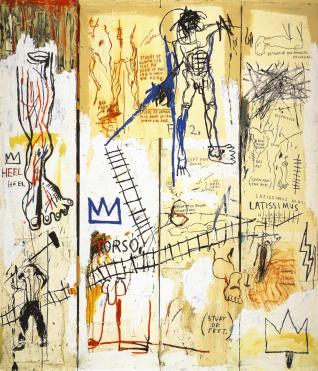

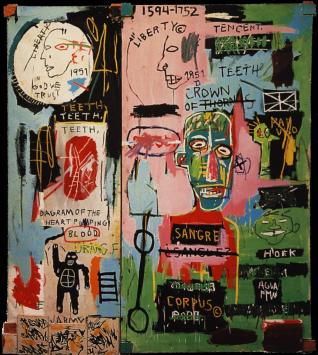

Indeed, there is much more to Basquiat’s work and intellect than meets the eye. He was a master of seemingly exposing things—the skeleton, the infrastructure, the core language of art and life—yet at the same time he occluded origins, influences, and skill with layers of a frenetic, always-in-a-hurry style.

He is, of course, an exquisite painter as seen in the minute details that swim to the surface in works such as Leonardo da Vinci’s Greatest Hits (1982) or the self-assured figure in St. Joe Louis Surrounded by Snakes (1982). But he also created engaging colorfield surfaces such as King Pleasure (1987). The drawings are phenomenal as well: some are spare, economical meditations, distillations of an idea into the meanderings of line; others are dense with deposits of marks and words. Basquiat’s almost overwhelming wordplay points to the profound conceptualism of his project, which is also visible in his rare three-dimensional objects. A piece like Untitled (Helmet) (1981), with black hair glued to a football helmet, riffs on David Hammon’s decade-long project in the same vein (check out Hammon’s Nap Tapestry [1978]). Basquiat’s Self Portrait (1985) reveals a surface cluttered with bottle caps that also echoes Hammon’s Higher Goals of the same year, a take on sports as both ghetto exit strategy and unattainable dream of black manhood. This dialogue with Hammons suggests Basquiat’s ease in speaking on the conceptual plane. It shows he didn’t have to be, but rather chose to be a painter.

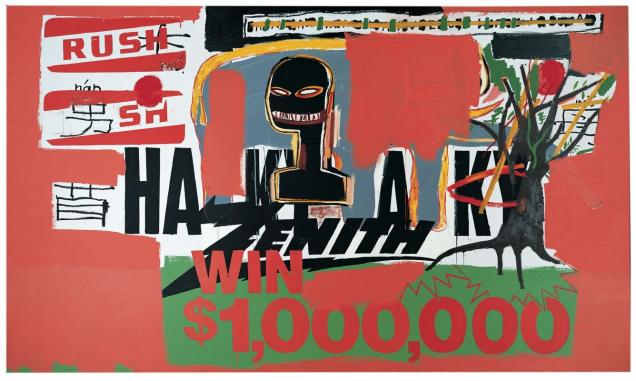

Part of Basquiat’s strategy of occlusion was “playing the primitive.” Selling shirts and objects in Washington Square Park. Affixing his name to urban corners, a middle-class boy from Brooklyn in the guise of a graffiti artist. Like John Guare’s protagonist, the gay hustler Paul, in the play Six Degrees of Separation, who makes his way into restricted social circles and homes by (mis)representing himself as the son of actor Sidney Poitier, Basquiat cruised into the art world on the runaway subway train of graffiti that was fueled by the stirrings of ’80s multiculturalism. Basquiat’s success and his investment in and comments on the art world’s star-making process of the art play a part in his fascination with brands and trademarks. As cultural critic José Esteban Muñoz has written, the tag “IDEAL,” which appears in the late works, points at once to a nationally recognized brand name of toy maker, to the false moral value placed in consumer products, and to the artist himself, the “I” who not only “deals” in “the same consumer public sphere” but makes his way to the top of the art world heap.

Basquiat and multiculturalism were the right combination in the right place at the right time. Indeed the critic Greg Tate has argued the same of Jimi Hendrix, who infused the British rock scene with new blood at a crucial moment. As Tate writes of Basquiat and crew at the turn of the 1980s, “Poised there at the historical moment when Conceptualism is about to fall and before the rise of the neoprimitive upsurge… hiphop’s train-writing graffiti cults pull into the station carrying the return of representation, figuration, expressionism, Pop-artism, the investment in canvas painting, and the idea of the masterpiece.” Yet interestingly, Tate also reminds us, Basquiat arrives not with the waves of bold color that signal outlaw urban painting, hues that would later characterize his own canvases, but with spare texts sprayed in black on peeling walls; he comes to us “as a poet.”

There is no question that Jean-Michel Basquiat, though he sometimes chose to obscure the fact, knew how to “paint Western art,” and was a formidable part of that tradition. Yet American painting, specifically, and the Western art tradition in general was only one source of Basquiat’s aesthetic. As Tate writes, “Initially lumped with the graffiti artists, then the Neo-Expressionists, then the Neo-Popsters, in the end Basquiat’s work evades the grasp of every camp because his originality can’t be reduced to the sum of his inspirations, his associations, or his generation…. He has consumed his influences and overwhelmed them with his intentions.” Indeed Basquiat is imbricated in, and draws on, not only the story of Western mark-and-art-making but the immense history of the globe itself, In Italian (1983) as one painting tells us, as well as in Greek, English, Ebonics, French, and Spanish. These paintings display modernity in their very facture but also overwhelmingly in their content. They constitute a chronicle of the world in modern form, connected through waves of history and histories of power. As scholar Arjun Appadurai has pointed out, artists like Basquiat “annex the global into their own practices of the modern.”

-- Kellie Jones, “Lost in Translation: Jean-Michel in the (re)mix,” in Kellie Jones et al, Eyeminded: living and writing contemporary art, 279-280.

Excerpt from The Philosophy of Andy Warhol

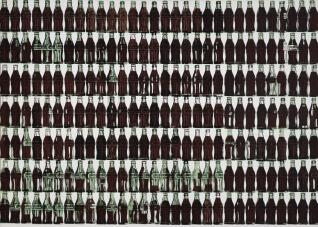

What’s great about this country is that America started the tradition where the richest consumers buy essentially the same things as the poorest. You can be watching TV and see Coca Cola, and you know that the President drinks Coca Cola, Liz Taylor drinks Coca Cola, and just think, you can drink Coca Cola, too. A coke is a coke and no amount of money can get you a better coke than the one the bum on the corner is drinking. All the cokes are the same and all the cokes are good. Liz Taylor knows it, the President knows it, the bum knows it, and you know it.

In Europe the royalty and the aristocracy used to eat a lot better than the peasants—they weren’t eating the same things at all. It was either partridge or porridge, and each class stuck to its own food. But when Queen Elizabeth came here and President Eisenhower bought her a hot dog I’m sure he felt confident that she couldn’t have had delivered to Buckingham Palace a better hot dog than that one he bought for her for maybe twenty cents at the ballpark. Because there is no better hot dog than a ballpark hot dog. Not for a dollar, not for ten dollars, not for a hundred thousand dollars could she get a better hot dog. She could get one for twenty cents and so could anybody else.

Sometimes you fantasize that people who are really up there and rich and living it up have something you don’t have, that their things must be better than your things because they have more money than you. But they drink the same Cokes and eat the same hot dogs and wear the same ILGWU clothes and see the same TV shows and the same movies. Rich people can’t see a sillier version of Truth or Consequences, or a scarier version of The Exorcist. You can get just as revolted as they can—you can have the same nightmares. All of this is really American.

The idea of America is so wonderful because the more equal something is, the more American it is. For instance, a lot of places give you special treatment when you’re famous, but that’s not really American. The other day something very American happened to me. I was going into an auction at Parke-Bernet and they wouldn’t let me in because I had my dog with me, so I had to wait in the lobby for the friend I was meeting there to tell him I’d been turned away. And while I was waiting in the lobby I signed autographs. It was a really American situation to be in.”

-Andy Warhol, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again, New York: Harcourt, 1975